OBJECTS TRANSFORMED DURING THE WAR

Museums play an important role in highlighting the realities and outcomes of war. In an article for the ‘Museum and Society‘ journal, museum professional James Scott, states that: ‘for many people, a visit to a military history museum is one of the main ways that they will learn about war, aside from its portrayal in education, the media or in film and television. The influence that military museums have in promoting a particular representation of war, is considerable.’ Considering this quote, the aim of this online exhibition is to analyse the Second World War through the lens of five unique and interesting objects. These objects demonstrate how individual lives were affected by acts or incidents during the war. All the objects in focus have either been transformed by an act of conflict or produced due to the circumstances around war.

Professor Jay Winter of Yale University reinforces the important role of military museums in depicting war. He states: ‘War museums are sites of contestation and interrogation. They can be vital and essential parts of our cultural environment if they enable visitors to ask questions about the limits of representation of violent events which cause human suffering on an unfathomable scale.’ Through sharing these five objects from our collection, we hope to encourage debate and ask questions about contentious topics relating to the Second World War. We also intend to shed new light on events that took place during the conflict.

Aircraft parts belonging to two of the most technologically advanced fighters of the Second World War, the Messerschmitt and the Supermarine Spitfire, are featured in this exhibition. This demonstrates that despite advancements in manufacturing and engineering, such as improving the armament on the Spitfire, or introducing an advanced cooling system in models of the Messerschmitt Bf 110, the individuals who were flying these machines were extremely vulnerable to being injured or killed by anti-aircraft fire, or due to the actions of enemy airmen. These aircraft parts reinforce the of being in air combat and the very possible reality of being shot down and captured or killed.

The exhibition will focus on five diverse objects and associated stories:

- A Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter aircraft that was shot down by a British fighter ace.

- Papier-mâché wood effect panels supposedly constructed by Italian Prisoners of War.

- The last flight of a Victoria Cross recipient and architect of Operation Chastise (the Dambusters Raid).

- Fragments from an anti-aircraft artillery shell that destroyed a V-1 flying bomb.

- Aircraft parts from a Spitfire flown by a Polish pilot that crashed near a small village in Northern France.

Messerschmitt BF 110

Messerschmitt BF 110 (3309) U8+DK was shot down by Sergeant W.T.E. Rolls of No. 72 Squadron on 2 September 1940 during the Battle of Britain. The aircraft crashed at 08:10 whilst escorting bombers to hit targets in Kent. The aircraft crashed near White Horse Wood, about seven miles west of Maidstone in Kent.

Schütz and Stüwe

Pilot Feldwebel Karl Schütz was killed and his gunner Gefreiter Herbert Stüwe bailed out. Upon landing Stüwe was intercepted by the Home Guard, taken as a Prisoner of War, and repatriated to Germany at the end of the Second World War. Karl Schütz was born on 1 July 1915 in Bavaria and became a fighter pilot, serving with 2 Staffel Zerstörergeschwader 26. He was originally buried in Snodland Cemetery near the scene of the crash, but later moved to the large German cemetery at Cannock Chase in Staffordshire (Reference Number: Block 1, Grave Number 60).

An intelligence report regarding the incident on 2 September 1940, produced by Squadron Leader Felkin, who oversaw the Air Intelligence section AI1 (K) during the Second World War)

The grave of Feldwebel Karl Schütz, killed on 2 September 1940 whilst piloting Messerschmitt BF 110 (3309) U8+DK

W.T.E Rolls

William Thomas Edward Rolls was born in Edmonton, in Middlesex on 6 August 1914. After being awarded a scholarship at The Latymer School, he enlisted in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in March 1939. After undertaking training at Gatwick and South Cerney, Rolls was signed off for operational duty in June 1940. He was assigned to No. 72 Squadron who moved to RAF Biggin Hill at the end of August 1940. Over the next few months, No.72 Squadron would be involved in some of the fiercest fighting of the Battle of Britain.

Two days after the arrival of No. 72 at Biggin Hill, on 2 September, Rolls shot down two aircraft within minutes during intense air battles over Kent. One of those was the Messerschmitt Bf 110 containing Feldwebel Schütz and Gefreiter Stüwe. In a combat report he wrote after the action, Rolls stated the following:

‘I took off from Croydon and followed Blue Section in wide formation and was instructed to climb to 15,000 (feet). We saw the enemy approaching from the S.E (south-east) and blue section led the attack on the bombers while I followed above them. I saw blue section break away and then… to south as I approached. I saw one Me110 leave the formation and dive on the tail of a Spitfire and as one other Spitfire was near enough I dived after it and came in at the Me110 from 150 (degrees) above and astern from port. I aimed at the Me110 port engine and put about 640 rounds into it. It caught fire and appeared to fall away with part of the wing and the (engine) went out on its back and went down with flames from the port wing. I had opened fire at 200 yards but did not see any return fire. I dived down at the back of it and saw 11 Do.17 below me at about 12’000 (feet). I had one in my sights and I fired all of my other rounds on it. The first aircraft blew to pieces and the engine caught fire. I closed my fire at about 175 yards to 50 yards and then dived again to… and went into a spin to avoid the Me109 behind. I found myself flying at 4,000 feet when I pulled out of the spin. Above me rather separated I saw 3 parachutes drifting down and to my starboard I saw the Do.17 coming down in flames and it crashed into the wood NE of Maidstone. I could not see the enemy again I went up to investigate the parachute. I saw that one was empty, another appeared to be a Sgt. Pilot with a mae west (parachute), and the other had no mae west and I circled around him and he landed near a factory in Chatham. I climbed up again to 3000 and made for base as we were ordered to return.’

a combat report written by Sergeant Rolls of No.72 Squadron after the incident on 2 September 1940

Rolls went on to become an ace during the Battle of Britain, a title given with at least five confirmed victories. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) with the citation appearing in the London Gazette on 8 November 1940:

‘This airman, after very short experience of operational flying, has taken his place with the best war pilots in the squadron. In each of his first two engagements he shot down two enemy aircraft and has in all destroyed at least six.’

After further service in the United Kingdom, Rolls served with distinction in Malta, where he was injured during a bombing raid in 1942. By the end of the War, he was credited with at least 17 confirmed victories, affording him the title of a triple ace. He retired from the RAF as a Flight Lieutenant and was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and Bar along with his DFM. In later life, Rolls worked in a civilian role at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research and died in 1988.

Souvenir Hunting

During the Battle of Britain, the country saw a huge spike in ‘souvenir hunting’. With rationing in affect, and certain materials or commodities hard to find, many people took to scouring through crash sites to find items to sell or use. This contributed to many aircraft parts appearing in museums or family collections, or even more recently on online auction sites!

This aircraft segment is a small part of the Battle of Britain Bunker’s collection, but it represents the intense fighting that was taking place in the skies of the south of England during the summer of 1940. It has been visibly altered by the crash, with the copper plating at the end of the segment bent in several places. The Bf 110 was made from metal which meant it was susceptible to corrosion over time. This segment looks visibly corroded in areas, which indicates it may have been in the ground for a while.

a part of Messerschmitt BF 110 (3309) U8+DK that was shot down on 2 September 1940

Italian Prisoners of War

From July 1941, Italian prisoners captured in campaigns in the Middle East were brought to Britain. Italian POWs were seen as a perfect antidote to labour shortages and therefore they were given jobs in low-employment areas, such as farming and agriculture. Despite some POWs maintaining loyalty to the dictator (and Prime Minister until 1943) Benito Mussolini, following the Italian surrender to the Allies in 1943, approximately 100,000 Italians volunteered to work as ‘co-operators’. These individuals were paid wages, given a fair amount of freedom and mixed with the local British population.

An interesting part of the collection at the Battle of Britain Bunker are these wood-effect panels, made from papier-mâché. They were supposedly made by Italian POWs during the Second World War. They adorned the walls of the Officers’ Mess at RAF Uxbridge for almost seventy years, until the base closed in 2010. The panels demonstrate something creative that was made during the unfortunate circumstances of War. Papier-mâché has a long history of military usage. In the First World War papier-mâché life-size figures were used on the Western Front as decoys to draw sniper fire. In the Second World War, with a shortage of metal readily available, paper drop tanks were introduced. These were aircraft fuel tanks made from papier-mâché, attached to the regular fuel system, and were used to extend the range of fighter aircraft. These attachable fuel tanks enabled fighters to fly further into occupied Europe on escort missions, providing close protection to the long-range bomber aircraft. This could indicate why papier-mâché was accessible to the Italian POWs if they had been working on constructing these fuel tanks.

It is unclear where these Italian prisoners were based, but there were a few POW camps in the borough of Hillingdon and neighbouring areas. English Heritage conducted a report in 2003, attempting to document the many POW camps in the country during the War. In 2008 author Sophie Jackson wrote a book, Churchill’s Unexpected Guests, examining the history of every camp from the period. Both sources mention the POW camp at Rayners Lane (which was a suburban district in the London Borough of Harrow). Rayners Lane was the most local camp to RAF Uxbridge containing Italian POWs.

Italian POWs started arriving there from November 1944, so they would have been classed as ‘co-operators’. This impact on the local population of Harrow was discussed in parliament. An official report from a debate in the House of Commons on Tuesday 28 November 1944, shows that the Conservative MP for Harrow, Norman Bower, was concerned about the impact on the local community and had heard reports about misdemeanours committed by the men. He requested that the ‘co-operators’ should not be allowed out after dark. His concerns were dismissed by other members of the Commons who demonstrated to him that there had been little to no complaints about the Italian men. 1 His Conservative colleague, Sir Reginald Blair (MP for Hendon) stated:

“Is my right hon. Friend aware that the hon. Member who represents the constituency in which Rayners Lane is situated has not received a single complaint, and that from his own personal investigations and other inquiries he believes that the behaviour of these Italian co-operators is very good indeed?”

The last prisoners left the Camp between July 1945 and September 1946. Many assimilated into the local area, opened businesses and remained in Harrow for the rest of their lives.

These wood effect panels were made from papier-mâché and were supposedly constructed by Italian Prisoners of War during the Second World War.

A group of Italian Prisoners of War relax at the N.144 workers camp, near London. Left to right, they are: Medical Officer Dr Salvatore Cirillo; Commander of the Camp, Colonel Hobby; Captain Gotelli (standing); Father Bazzoli, the Camp Chaplain; Major Green, assistant to Colonel Hobby; and Corporal Cocmazzi, acting as waiter. (1945) © IWM D 26742

Guy Gibson Mosquito

Part of the de Havilland DH. 98 Mosquito light bomber which crashed near Steenbergen in the Netherlands on the night of 19 September 1944.

The incident

Late in the evening of 19 September 1944, a de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito light bomber, piloted by Wing Commander Guy Gibson VC was hit by machine gun fire and crashed near Steenbergen in the Netherlands, killing Gibson and his Navigator, Squadron Leader James Warwick DFC. In the Bunker’s collections there is a piece of the damaged aircraft recovered from the site.

Richard Morris in his book ‘Guy Gibson’ (1994) states that Gibson had requested a change of aircraft at RAF Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire, on the same evening as the fatal incident. He wrote: ‘At Woodhall they were told that Mosquito R KB213 had been prepared for them and now stood loaded with target indicators, (flares designed to provide visibility for Bomber Command to aim at their targets). Surprisingly, Gibson rejected this aircraft and requested another. It was agreed that he should take Mosquito E KB267.’

Gibson and Warwick were part of a larger force due to conduct a night bombing raid over the German city of Mönchengladbach, near the Dutch border. The pair took off at 19:51 as part of a formation of 10 Mosquitos and 227 Avro Lancaster bombers.

When the Raid arrived at the target, they encountered a series of issues, including problems with the target indicators and engine failure for one of the bombers. Gibson attempted to mark the target himself but failed. There was scattered bombing over the area and the raid concluded at 21:58.

Gibson’s aircraft crashed close to a sugar factory near Steenbergen at around 22:30. The German occupiers quickly discovered the crash site and recovered human remains, plus a sock labelled ‘Guy Gibson’ and Squadron Leader Warwick’s dog tags. Gibson was officially posted as missing on 29 November. The two men are buried in Steenbergen’s Catholic Cemetery and the graves are under care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. More information can be found here:Steenbergen-En-Kruisland Roman Catholic Cemetery | Cemetery Details | CWGC

Theories

It has been speculated that Mosquito E KB267 was brought down by light anti-aircraft fire, or even pilot error or loss of fuel, however, until recently no theory of the cause of the incident has been conclusively proven. Contemporary theories of friendly fire have also been suggested. In 1992, a sergeant in Gibson’s formation was recorded on tape admitting to mistaking the Mosquito for an enemy aircraft and bringing it down in the same location as the crash site. This was reported by the BBC and other media outlets in 2011 but has yet to be corroborated by historians.

This ambiguity surrounding the event is summarised by John Nicol in his book ‘Return of the Dambusters’ (2015):

“Whether he was hit by flak or fire from a night fighter, suffered a mechanical failure, made an error due to his unfamiliarity with the Mosquito he was flying, or simply ran out of fuel is unknown, but his aircraft crashed at Steenbergen in the Netherlands at 10:30 that evening, and Gibson was killed instantly.”

Gibson

Wing Commander Guy Gibson, caption: Wing Commander Gibson with members of his crew (1943). Left to right: Wing Commander Guy Gibson, VC, DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar; Pilot Officer P M Spafford, bomb aimer; Flight Lieutenant R E G Hutchinson, wireless operator; Pilot Officer G A Deering and Flying Officer H T Taerum, gunners. © IWM TR 1127

Guy Gibson was born in India in 1918, and his family moved back to England at the age of three. After being educated at The University of Oxford, he joined the RAF in 1936. He became a distinguished bomber pilot during the early stages of the Second World War, and during April to September 1940, he completed 34 operations in just five months.

By the time of Operation Chastise in 1943 (more commonly known as the Dambusters Raid), Gibson was already heavily decorated and had a reputation within Bomber Command as one of the best pilots in the force. He was selected to command ‘Squadron X’ who were made up of hand-picked bomber personnel, to undertake rigorous training to perform a series of low-level bombing attacks on German dams in the industrial Ruhr region.

The attacks took place over the night/ early morning of the 16/17 May. Using the bouncing bomb, a new design of bomb which was designed to bounce over obstacles to hit a target, the assaults on the Möhne and Eder Dams caused heavy disruption to German industry. Controversially the bombing caused high civilian casualties in the area, as many forced labourers were killed by the ensuing flood wave. Gibson’s leadership in the raid was recognised with the award of the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy.

Gibson’s fame increased dramatically after the Raid. The Allies were keen to promote the ‘Dambusters’ and many saw this strike against the industrial heartland of Germany as a morale boost. In February 1944 Gibson appeared on Desert Island Discs, a popular BBC radio show, and undertook a media tour of the US and Canada. Throughout this time, Gibson was itching to get back to flying combat missions and lobbied hard to return to the fighting.

Gibson’s death at the age of 26 in 1944 made him one of the most high-profile airmen to be killed in the Second World War.

Warwick

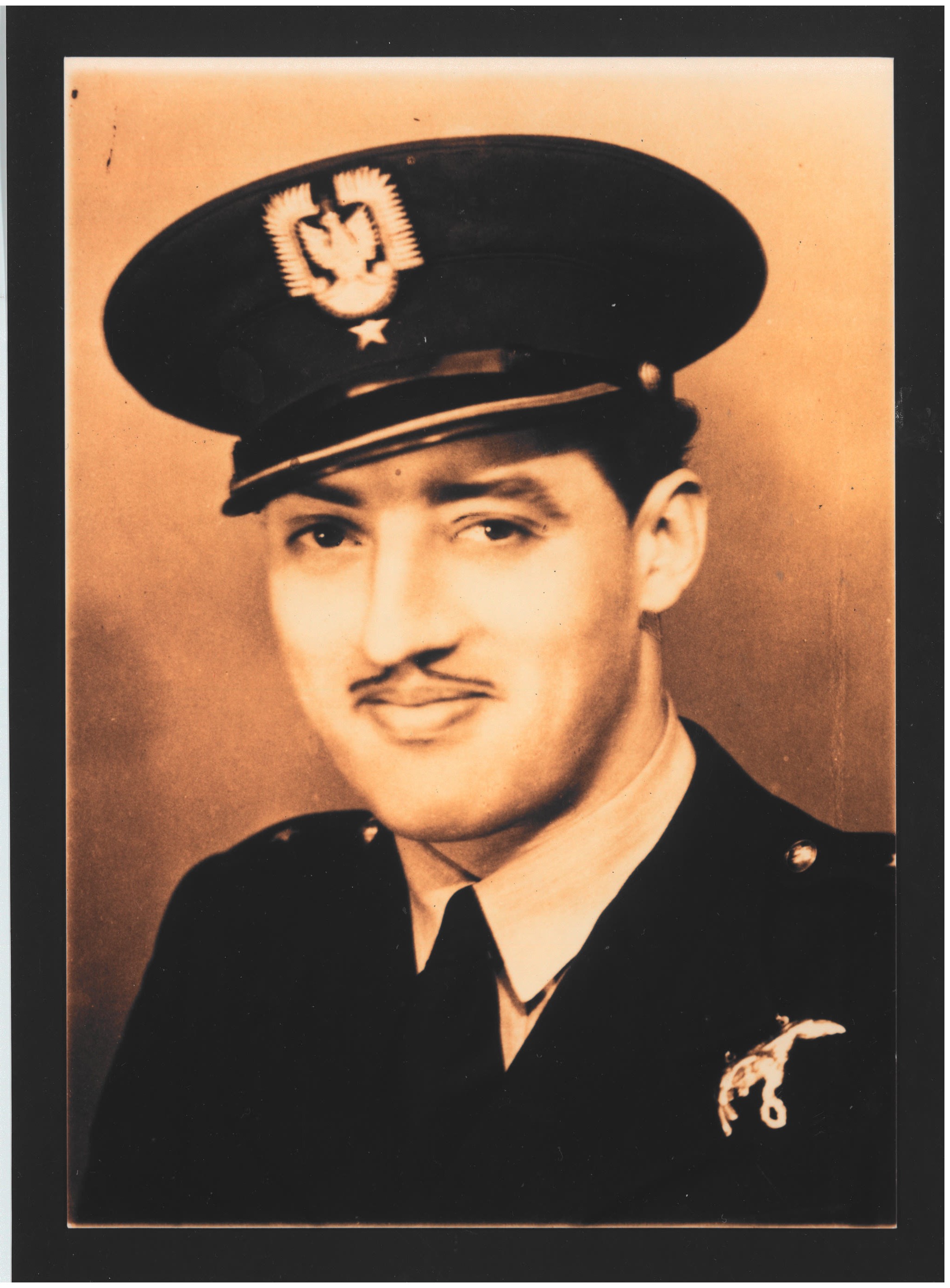

Jim Warwick DFC, caption: Jim Warwick DFC, who was killed with Guy Gibson at Steenbergen, Netherlands on 19 September 1944

James Warwick was born in Belfast in 1921. After schooling he moved to London to work for the Air Ministry. In 1941 he joined the Royal Air Force and was posted to Canada to start navigational training. In 1943 he was posted back to the United Kingdom and subsequently joined No. 49 Squadron, where Warwick performed his first operational flight. His service with No.49 stretched beyond a year and during this time he was promoted to Pilot Officer. He was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) on 15 February 1944 for operational service over Germany.

He was subsequently promoted to Squadron Leader and assigned as Station Navigational Officer at RAF Coningsby as part of 54 Base. In this role he was meant to be signed off operational duties, but a chance meeting at the Officer’s Mess with Guy Gibson on the afternoon of 19 September 1944, unfortunately meant that he was Gibson’s navigator that evening. Gibson had been looking for a navigator, as the one assigned to him had not been available. It is now known that Gibson had been informed that Warwick had not flown in a Mosquito before and was meant to be off operational duty.

James Warwick was just 23 years old when he was killed in the crash over Steenbergen.

Anti-Aircraft shell fragments that brought down a V-1 flying bomb.

Shell fragments from an anti-aircraft shell that destroyed a V-1 flying bomb over Bromley in 1945

These shell fragments are all that remain of an anti-aircraft shell, fired at a V-1 flying bomb over Bromley, Greater London in 1945. The V-1 and V-2 weapons were German long-range artillery missiles used for strategic bombing of British cities. The V-1 was a small aircraft without a pilot and the V-2 was a rocket, and Nazi Germany called them Vergeltungswaffe (retaliation weapons). The V-1 was deployed to Britain in June 1944 and the V-2 followed in September of the same year.

The V-1

The first V-1 weapon was launched on 13 June 1944, hastily deployed a week after the successful invasion of occupied Europe by Allied forces. They were used with such effectiveness, that many Londoners referred to the deployment of the V Weapons as a “second Blitz”, after the Luftwaffe’s targeted bombing campaign a few years earlier (September 1940-May 1941). The V Weapons continued to terrify the population in the south of England and cause immense damage to property and infrastructure until the late stages of the Second World War.

The V-1 was jet-powered and nicknamed the ‘doodlebug’ due to its distinctive engine noise. Fighter Command nicknamed them ‘diver’ due to them diving towards the ground when they appeared over London. The V-1 was the first mass produced cruise missile in history. It measured about 25 feet long, not including its long tailpipe jet engine. It was typically launched from catapult ramps, or very rarely, launched from an aircraft. It carried an explosive warhead that weighed about 850 kilograms. It could travel at a speed of about 360 mph and had an average range of 150-160 miles.

More than 8,000 V-1s were launched against London from 13 June 1944 to 29 March 1945. It is calculated by sources including Bomb Census survey records conducted by the British wartime government, that about 2,400 found their targets. 6,184 people lost their lives in London as a direct result of a V-1 attack.

18 June 1944

At 11:20am on Sunday 18 June 1944, a V-1 flying bomb hit the Guard’s Chapel near Buckingham Palace, where a mixed civilian and military congregation were worshipping. This was the single most catastrophic loss of life of the V weapons campaign and 121 people lost their lives.

The building had existed since 1838 and was known as the Royal Military Chapel. It formed part of the Wellington Barracks adjacent to St James’s Park, which had been home to the Brigade of Guards, (a formation of the British Army which existed from 1856 to 1968) since the mid-19th Century.

One of the fatalities was Section Officer Cornelia Thorn of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). Thorn was born in New York in 1911 and was killed alongside her husband, Major Terence Thorn MC, of the Royal Engineers in the bombing of the Chapel. Her mother-in-law, Mrs Elizabeth Amy Thorn was also killed in the disaster. In 1951, this bust of a cavalry officer raising their sword, was dedicated to the WAAF by Thorn’s mother, Estelle D. Vanderhoof, in memory of her daughter. This object is now part of the Bunker collections and is on display in the underground museum.

This bust of a cavalry officer was presented to the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force in memory of Section Officer Cornelia Thorn, who was killed when a V1 bomb hit the Guard’s Chapel near Buckingham Palace on Sunday 18 June 1944

Counter measures

After the first V-1 rockets began to hit London, Fighter Command realised they needed to react quickly and decisively. Various countermeasures that had been successful during the Battle of Britain in 1940, were deployed to deal with the new threat. Some of the defence methods used were anti-aircraft guns, barrage balloons, the Royal Observer Corps, and even fighter aircraft interception. The world’s first integrated air defence network – the Dowding System – could also be used to counter Nazi Germany’s V Weapons.

Radar was able to detect the V Weapons, partly due to the development of the gun-laying radar, inspired by the cavity magnetron, which had allowed radar systems to detect objects of a small size moving at high speed. This was a decisive breakthrough in radar technology and allowed the Royal Artillery more detailed information on the range and size of the V Weapons. Moreover, the development of the Proximity Fuse, which allowed the anti-aircraft shells to explode when close to its target, greatly improved the chance of the V Weapons being damaged.

Despite these developments, it was still extremely difficult for anti-aircraft gunners to hit these targets. This was mainly due to speed as a V-1 flying bomb could get up to 360mph, and the low altitude they were flying at, which was usually around 2,000 to 3,000 feet. Often the Royal Artillery’s guns could not move fast enough to shoot the targets.

These fragments are a legacy of how despite the difficulties presented, anti-aircraft guns helped bring down this particular V-1 rocket over Bromley, potentially preventing severe loss of life.

Iliński

Disclaimer: Some people may find images in this section distressing

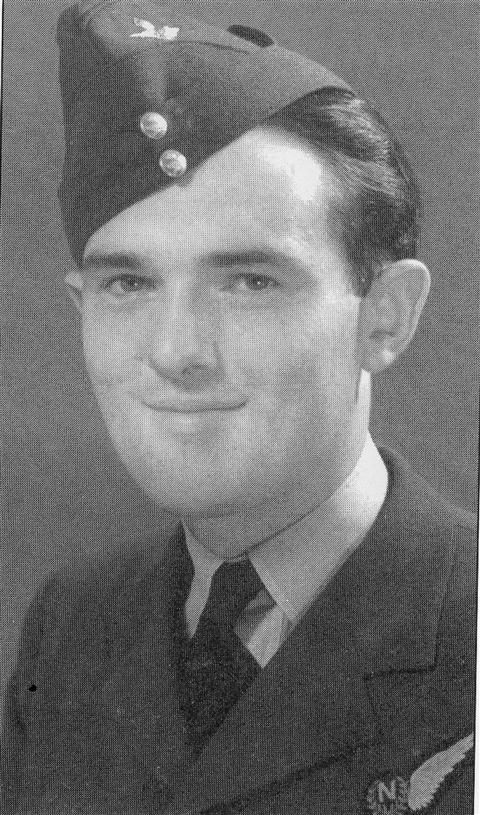

Flight Lieutenant Olgierd Iliński

Spitfire R7161 was shot down over Maulévrier in France, on 16 August 1943. The pilot, Olgierd Iliński, was tragically killed aged 29. Iliński had been serving with No. 308 (City of Kraków) Squadron.

Iliński was commissioned from the Polish Air Force College at Dęblin , on 1 September 1939. Upon the fall of Poland, he escaped to France via the Mediterranean. In France he underwent more training as a fighter pilot, both at Versailles and at Bussac, near Bordeaux. After escaping France in June 1940, he was posted to No. 55 Operational Training Unit at RAF Aston Down to complete his training. Iliński’s first operational posting was with No. 605 Squadron, a Royal Auxilliary Air Force Squadron, in 1941. He was reposted to No. 302 (City of Poznań) Squadron and then No. 303 (Kościuszko) Squadron, before his final operational posting with No. 308 (City of Kraków) Squadron. By the time of his death in August 1943, Iliński was an experienced fighter pilot with over two years of combat experience.

On the morning of 16 August 1943, Iliński was acting as part of a close escort to Martin B-26 Marauder bombers as part of a ‘Ramrod’ operation. The definition of a ‘Ramrod’ in the context of the Second World War was: ‘short range bomber attacks to destroy ground targets.’ The aircraft formed over Beachy Head in East Sussex at 10:20, crossed the French coast shortly after, and were met by large numbers of Luftwaffe aircraft. Fierce fighting took place near the targets at Bernay St Martin airfield and Iliński was shot down and killed near Maulévrier, when he was attempting to return home.

In The Polish Air Force at War, historian Jerzy Cynk recalls the operation in which Iliński lost his life. He states the following:

‘The squadron’s only encounter with the enemy, during the Ramrod on 16 August, ended tragically. Its 12 Spitfires, giving cover to Marauders (an American medium ranged bomber), were attacked by a large formation of Fw 190s (enemy Focke-Wulf fighter aircraft) and in a desperate battle lost three of their number in exchange for only one enemy damaged – by Flight Sergeant Stański. Flying Officer Iliński (in Spitfire R7161) was killed. Pilot Officer Wiesław Mejer (in Spitfire AB803) was shot down and made POW, and Flight Sergeant Władysław Sznapka (in Spitfire W3404 ditched in the sea, but was rescued. Another pilot Flight Sergeant Wacław Korwel was wounded, and his Spitfire (BM137) damaged in a forced landing.’

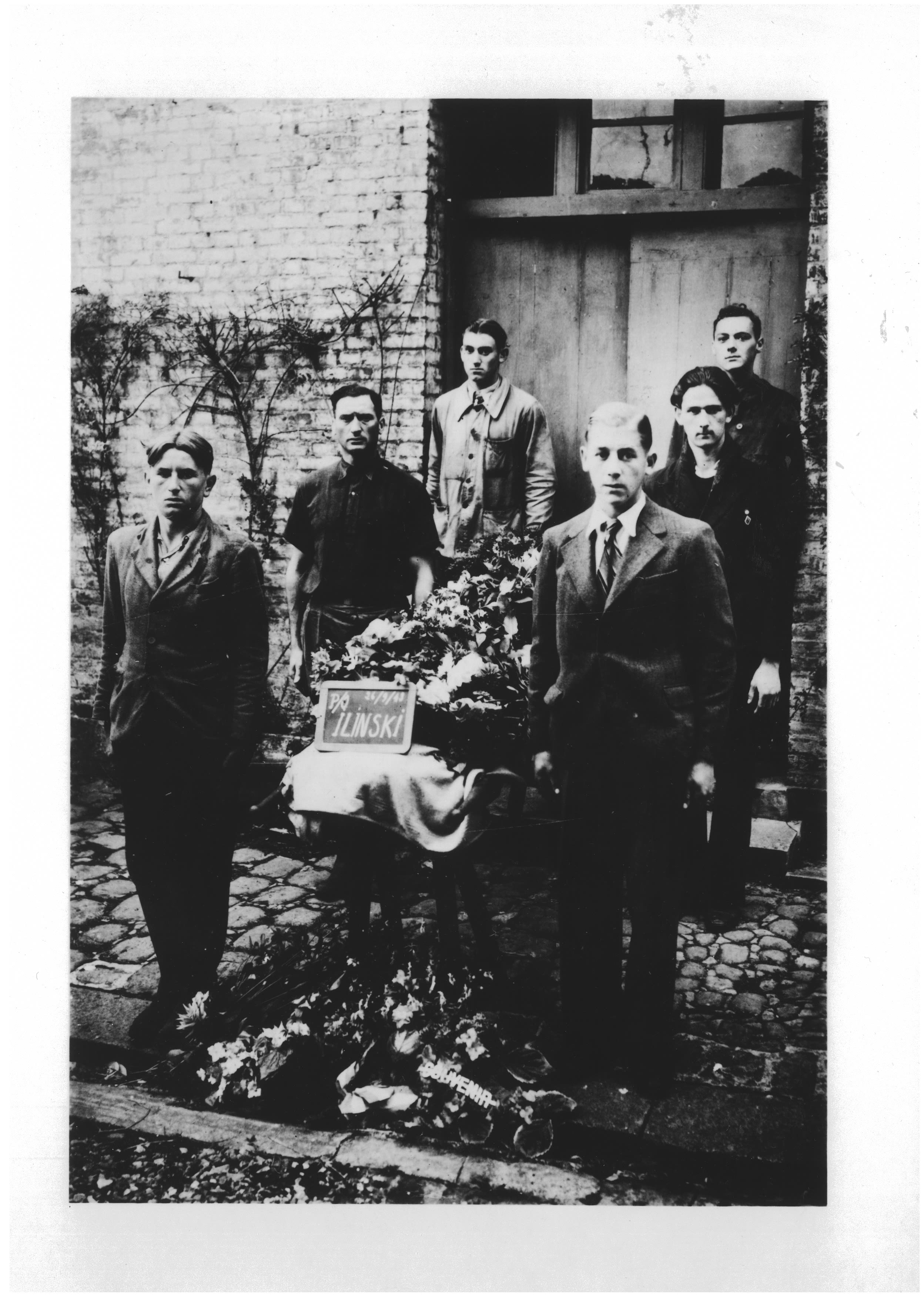

After witnessing the crash, local residents, with assistance from the Luftwaffe, organised for the retrieval of Iliński’s body. They used a large wooden rig and a pulley system to recover him. The aircraft was sunken into the muddy ground, and it took five weeks for the body to be carefully removed. He was taken to Saint Marie Cemetery in Le Havre where he rests today.

Artefacts that were found at the crash site are on display in the Polish Air Force gallery at the Battle of Britain Bunker, as a permanent memorial to Olgierd Iliński. The surviving aircraft parts include the Spitfire fuselage and tyre. Evidence of the crash can be seen on both items, with discolouration and mud visible. There is also damage to the metal casing on the fuselage, caused by impact of the Spitfire into the ground. The fleece-lined leather shoe has one side of it missing and wire mesh lining has been added to ensure that the boot keeps its shape. The damaged boot shows the devastating effect of the crash and is a sobering reminder of the realities of aerial combat at the time.

The Iliński collection is on long term loan from the Polish Air Force Memorial Committee and parts of it are on display at the Battle of Britain Bunker.

Parts of Spitfire R7161 which was shot down over Maulévrier in France, on 16 August 1943. The Spitfire was piloted by Flight Lieutenant Olgierd Iliński who was killed

six men stand by the coffin of Flight Lieutenant Olgierd Iliński, who was killed in Spitfire R7161 over Maulévrier in France, on 16 August 1943

an official Ministry of Defence letter from 1979, detailing the action that Lieutenant Olgierd Iliński was killed in

The Polish Air Force exhibition at the Battle of Britain Bunker